“Like the light of the sun, it beautifies all things on which it shines, and is no less welcome in the palace than in the humblest homes” –

Lewis Latimer 1891

Lewis Latimer

Thomas Edison is widely recognized the world over as the inventor of the light bulb, but the story is much more complicated than that. African-American inventor Lewis Latimer drew the first electric light blueprints and patented the method for making carbon filaments, allowing light bulbs to burn for hours instead of minutes. Lewis Howard Latimer was born in 1848. He was an African American inventor and innovator in the electric lighting industry.

His parents, George and Rebecca Latimer, escaped slavery in 1842, journeying from Virginia to Massachusetts. When George’s owner showed up in Boston to reclaim his property, the organized abolitionist movement there rallied in full force, making the Latimer case the cause celebre of their mission, starting the Latimer Journal and North Star to keep the public abreast of the case and raising the money to purchase his freedom. The case leads to a petition, signed by 65,000 citizens of the Commonwealth, insisting that a law should be passed forbidding the State of Massachusetts from detaining fugitives from slavery and that amendments to the Constitution of the United States be proposed by the legislature of Massachusetts to definitively separate the people of Massachusetts from all connection with slavery. The petition did result in such an act, effective for the State, but was ultimately unsuccessful at the Federal level.

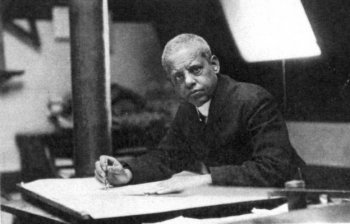

As a boy Latimer worked in his father’s barbershop in Chelsea, Massachusetts. When the Civil War broke out, his older two brothers enlisted and so did he, serving in the Navy and teaching himself technical drawing. After an honorable discharge in 1865, he worked for patent attorneys Crosby Halstead & Gould. Although Latimer was hired as an office boy, earning $3.00 each week, he cultivated drafting skills in his spare time until he was qualified for blueprint work. Latimer brainstormed his own work, patenting in 1874 a “pivot bottom” for water closets on trains and was promoted to head draftsman, earning $20.00 a week (the equivalent to the modest annual sum of about 22k in today’s money). In 1876, Latimer was sought out as a draftsman by a teacher for deaf children. The teacher had created a device and wanted Lewis to draft the drawing necessary for a patent application. The teacher was Alexander Graham Bell and the device was the telephone. Working late into the night, Latimer worked hard to finish the patent application, which was submitted on February 14, 1876, just hours before another application was submitted by Elisha Gray for a similar device. His high-caliber draftsmanship impressed Alexander Graham Bell, who sought the firm’s services to patent his 1876 invention, the telephone. Latimer was entrusted to handle the complicated illustrations.

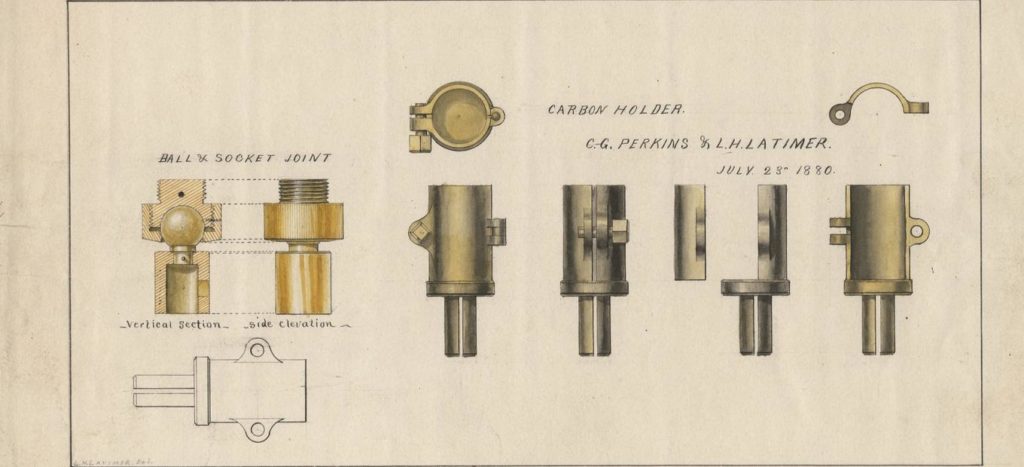

In 1880 Latimer was hired as the assistant manager and draftsman for U.S. Electric Lighting Company owned by Hiram Maxim and moved to Bridgeport, Connecticut, . Maxim was the chief rival to Thomas Edison, the man who invented the electric light bulb. The light was composed of a glass bulb which surrounded a carbon wire filament, generally made of bamboo, paper or thread. When the filament was burned inside of the bulb (which contained almost no air), it became so hot that it actually glowed.Thus by passing electricity into the bulb, Edison had been able to cause the glowing bright light to emanate within a room. Before this time most lighting was delivered either through candles or through gas lamps or kerosene lanterns. Maxim greatly desired to improve on Edison’s light bulb and focused on the main weakness of Edison’s bulb – their short life span (generally only a few days.) Latimer set out to make a longer-lasting bulb. Latimer devised a way of encasing the filament within a cardboard envelope which prevented the carbon from breaking and thereby provided a much longer life to the bulb and hence made the bulbs less expensive and more efficient. This enabled electric lighting to be installed within homes and throughout streets. Latimer’s abilities in electric lighting became well known and soon he was sought after to continue to improve on incandescent lighting as well as arc lighting. Eventually, as more major cities began wiring their streets for electric lighting, Latimer was dispatched to lead the planning team. Under Maxim, Latimer patented the threaded wooden socket for light bulbs and supervised the installation of the first electric street lights and electric plants in New York City, Philadelphia, Montreal, and London.

In 1882 Latimer began working for the Olmstead Electric Lighting Company of Brooklyn as superintendent of lamp construction and created the Latimer Lamp. Later he worked for the Acme Electric Company in New York and in 1883, Latimer became an engineer at the Edison Electric Light Company in Brooklyn. He had the distinction of being the only African American member of “Edison’s Pioneers” – Thomas Edison’s team of inventors. The Edison Electric Illuminating Company of Brooklyn provided electricity to the homes and businesses of Brooklyn and fabricated conductors for other plants like those in Milan, London, and Paris. Latimer continued to display his creative talents over the next several years. In 1894 he created a safety elevator, a vast improvement on existing elevators. He next received a patent for Locking Racks for Hats, Coats, and Umbrellas. The device was used in restaurants, hotels and office buildings, holding items securely and allowing owners of items to keep them from getting misplaced or accidentally taken by others, and the 1905 Book Supporter,

In 1919 the Edison Electric Light Company merged with Kings County Electric Light and Power Company to form Brooklyn Edison (Brooklyn Edison merged with Consolidated Edison and other companies between 1936 and 1960 In the early 1930s, the Brooklyn Edison Company created a 10 room house called the Edison Wonder House in the lobby of its showroom at Pearl Street in Brooklyn, New York. The house demonstrated the possibilities of electricity in the home. The demonstration home was not intended to be copied, but to provide future homeowners with ideas. Some special features of the house included lighting that was a sight saver, unusual clocks, a built-in aquarium, and a magic door that opened through the operation of an electrical eye.)

Latimer also developed other inventions of his own, co-patenting an electric lamp with Joseph V. Nichols in 1881, and, most important, refining light-bulb technology in 1882. In 1884 he was invited to work for Maxim’s arch rival, Thomas Alva Edison, in New York.

An expert electrical engineer, Latimer’s work for Edison was critical for the following reasons: his thorough knowledge of electric lighting and power guided Edison through the process of filing patent forms properly at the U. S. Patent Office, protecting the company from infringements of his inventions; Latimer was also in charge of the company library, collecting information from around the world, translating data in French and German to protect the company from European challenges. He became Edison’s patent investigator and expert witness in cases against persons trying to benefit from Edison’s inventions without legal permission.

Latimer also wrote the book, Incandescent Electric Lighting: A Practical Description of the Edison System. Published in 1890, it was extremely popular as it explained how an incandescent lamp produces light in an easy-to-understand manner. On February 11, 1918, Latimer became one of the 28 charter members of the Edison Pioneers, the only African-American in this prestigious, highly selective group. After leaving Edison, Latimer worked for a patent consultant firm until 1922 when failing eyesight caused an end to his career. His health began to fail following the death of his beloved wife Mary Wilson Latimer in 1924. To cheer and encourage him to carry on, his children, two daughters, had a book of his poems printed in 1925 in honor of his 77th birthday.

The poems are beautifully sensitive and complement Latimer’s designation as a “Renaissance Man” who painted, played the flute, wrote poetry and plays. Among the collection of poems was one written in tribute to his departed wife.

Ebon Venus

“Let others boast of maidens fair,

Of eyes of blue and golden hair;

My heart like needles ever true

Turns to the maid of ebon hue.

I love her form of matchless grace,

The dark brown beauty of her face,

Her lips that speak of love’s delight,

Her eyes that gleam as stars at night.

O’er marble Venus let them rage,

Who sets the fashions of the age;

Each to his taste, but as for me,

My Venus shall be ebony.”

Lewis Howard Latimer settled in Flushing, New York, and lived there until his death in 1928. Latimer’s house, where he lived from 1903 to 1928, still stands in Flushing, and is open to the public as the Lewis H. Latimer House. He was an active member of the local community, teaching English and drafting to immigrants at the Henry Street Settlement in 1906. In 1968, Latimer was posthumously honored by the borough of Brooklyn when a public school was named after him.

Latimer was also a member of the ‘Students Club of Brooklyn: a society comprised entirely of prominent black citizens dedicated to the best efforts, education, science, social and political economy, pedagogy, history, and questions affecting the colored American. In 1901, Latimer joined his colleagues at the headquarters of the SCB (then located at 184 Adelphi Street) to listen to an address presented by its president, inventor, Samuel R. Stratton (maternal grandfather of the singer Lena Horne) and engage in a general discussion regarding a proposition to offer formal education to black people along the lines of “manual training courses and in the trades, thus lifting them from the lowly level of much of their labor and bring them into a condition to better meet competition.”

Reference:

The African American Desk Reference

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

Copyright 1999 The Stonesong Press Inc. and

The New York Public Library, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Pub.

ISBN 0-471-23924-0

Watch a short documentary on Latimer

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oB3Mdw2lqkA