COLORED SCHOOL No. 1

By Carl Hancock Rux

“No great amount of research is required to find that one of the chief reasons for the intelligent and aggressive action of New York Negroes and for their position of leadership during the period between the Revolutionary and Civil wars lay in education.”

– James Weldon Johnson

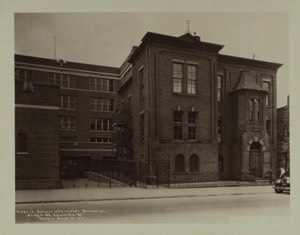

In 1827, seventy odd years before Brooklyn would become annexed by New York City, the area now known as Fort Greene, Brooklyn, became the first district on the island to erect a school for the formal education of African Americans. Colored School No. 1 was founded in clapboard house in the area now know as Fort Greene Brooklyn: a free school for the instruction of African children. Located on Willoughby Street and Raymond in an area of Fort Greene heavily populated by African Americans, Colored School No. 1 numbered between 250 and 300 African American pupils, and was once cited by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle as “one of the best conducted institutions under the Education Department”. The building that housed the school for its first fifteen years, however, was described by its principal as “a dilapidated old wooden building. The accommodations almost too small from the start.” The school was later moved to a sturdy brick structure that cost $25,000, and is occupied by 450 scholars. They are divided into two departments, namely, primary and grammar— the first, as usual; being on the ground floor and the second on the floor above, with room for about one hundred more pupils. Colored School No. 3 (the building still existent) was erected in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn in 1879, and was by then, the only remaining school exclusively used by African American students.

School No 1

African Americans constitute one of the longer-running ethnic presences in New York City. The majority of the African American population were forcibly abducted from their villages in West and Central Africa and brought to the American South via the Atlantic slave trade, with smaller portions of the population were voluntary immigrants from Caribbean, Latin American, and modern Sub-Saharan African nations. In New York City, the formal education of the African in America was institutionalized as the thirteen British colonies emerged as a new independent nation to be known as the United States of America, and, under the leadership of General George Washington, 13 states replaced the Articles of Confederation with the Constitution of the United States of America. With its amendments it remains the fundamental governing law of the United States today.

Following the establishment of the public school system in Brooklyn in 1850, the African Free School was incorporated into the system and renamed Colored School No. 1. In 1887 following the end of the segregated schools in Brooklyn, the Colored Schools were renamed, and Colored School No. 1 became Public School 67.

By the late 1800’s, colored schools (as they were then called) numbered about four in the city of Brooklyn—No. 1 on Willoughby and Raymond Street in Fort Green; No. 2 on Troy Avenue and Bergen Street In Crown heights; No. 3 on Union and South Third Street, in Williamsburg; and No. 4 on High street near Pearl street in what is today known as Downtown Brooklyn—with a registered number of approximately five to six hundred African American students, and a daily attendance of about four hundred across the four schools. The schools were presided over by African American principals and taught by African American teachers, and were considered proportionately as successful as the schools devoted to white children. Children of noticeable mixed ethnicities (African American and White) had the privilege of attending of white schools, but those of perceived “pure negro blood” were restricted to the colored schools.

In 1847, the tradition of tuition-free colleges and schools was captured best by its founder, Townsend Harris, who proclaimed at the founding of the Free Academy (the predecessor to the city’s first municipal college) that the city should: “Open the doors to all—Let the children of the rich and the poor take their seats together and know of no distinction save that of industry, good conduct and intellect.” This mission was realized primarily through a free tuition policy that was maintained at the city-supported municipal colleges for 129 years.

That same year, the Commissioner of the Board of Education demanded that $5,000 appropriated for the colored district, (approximately $158,000 in today’s currency) be placed in the hands of the treasurer for the betterment of Colored Schools. With funds in place, Colored School No. 1 was the largest colored school in Brooklyn with an attendance of about two hundred students (one hundred and twenty five students in the primary school and the remainder in the higher). Though called Colored Schools, all of the schools had a spattering of white students as well (three or four registered in each), and prided themselves in having “no distinction” between qualities of education in comparison to white schools.

School No 1

Fort Green’s Colored School was not without precedent. One year earlier, a free school for the instruction of African children had lately been formed in Newark, New Jersey under the title of The Kosciusko School, named after the distinguished champion of civil liberty general Kosciusko who by his will, gave to Thomas Jefferson the available amount of $13,000 dollars to be employed in liberating enslaved Africans, and bestowing upon them such an education, “as, to use his own words, would make them better fathers, better mothers, better sons and better daughters.” Long before Brooklyn was officially annexed into the City of New York, The New York Society’s mission for the abolition of slavery predated the official union of the United States. By the 1760s, the American colonists began to wage a war of words and resistance against the British colonial government. The language of the dissenting colonists soon became the language of African Americans as well in their fight for personal freedom. Their poems, letters, and petitions used the rhetoric of the age to appeal for slavery’s abolition in the rhetoric of the age, noting King George had “waged cruel war on human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating and carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither.” Though not a war over slavery, a few white colonists publicly noted the paradox between the patriots’ demands for liberty and the widespread acceptance of slavery. Prominent Massachusetts’s lawyer James Otis called the slave trade “the most shocking violation of the law of nature” and posed a series of rhetorical questions which challenged the logic of enslaving blacks because of their physical characteristics. Before his death, Connecticut lawyer John Allen, in the Watchman’s Alarm questioned the values of his fellow colonists, chiding them for “enslaving [their] fellow creatures . . .. What is a trifling three-penny duty on tea compared to inestimable blessings of liberty to one captive?”

In a letter written Jan. 18, 1773, Patrick Henry of Virginia, President of the Virginia Abolition Society, wrote: ” Believe me, I shall honor the Quakers for their noble efforts to abolish slavery. It is a debt we owe to the purity of our religion to show that it is at variance with that law that warrants slavery. I exhort you to persevere in so worthy a resolution.” In the preamble to the act prohibiting the importation of slaves into Rhode Island (June, 1774) the following was written— “Whereas, the inhabitants of America are generally engaged in the preservation of their own rights and liberties, among which that of personal freedom must be considered the greatest, and as those who are desirous of enjoying all the advantages of liberty themselves, should be willing to extend personal liberty to others”. October 20, 1774, the continental congress passed a law to no longer “import nor purchase any slaves” after the “first day of December next, after which time we will wholly discontinue the slave trade, and we will neither be concerned in it ourselves, nor will we hire our vessels, nor sell our commodities or manufactures, to those who are concerned in it.”

In 1776, Dr. Stephen Hopkins, then at the head of New England divines, published a pamphlet entitled: “An Address to the owners of negro slaves in the American colonies,” in which he wrote: “The conviction of the unjustifiable practice of (slavery) has been increasing and greatly spreading of late, and many who have had slaves, have found themselves so unable to justify their own conduct in holding them in bondage, as to be induced to set them at liberty. May this conviction soon reach every owner of slaves in North America! Slavery is, in every instance, wrong, unrighteous, and oppressive, a very great and crying sin—they’re being nothing of the kind equal to it on the face of the earth.”

The colonies declared their independence from the Crown as “free and independent States” and the continental congress ordered a pamphlet to be published, entitled, ” Observations on the American Revolution,” from which the following is an extract: ” The great principle (of government) is and ever will remain in force, that men are by nature free; as accountable to him that made them, they must be so: and so long as we have any idea of divine justice, we must associate that of human freedom. Whether men can part with their liberty, is among the questions which have exercised the ablest writers; but it is conceded on all hands, that the right to be free can never be alienated—still less is it practicable for one generation to mortgage the privileges of another.” The Pennsylvania Act for the Abolition of Slavery, passed March 1, 1780, declared.” We conceive that it is our duty, and we rejoice that it is in our power, to extend a portion of that freedom to others which has been extended to us. Weaned by a long course of experience from those narrow prejudices and partialities we had imbibed, we find our hearts enlarged with kindness and benevolence towards men of all conditions and nations. Therefore be it enacted, that no child born hereafter be a slave,”

Thomas Jefferson (a slave owner) wrote ” The spirit of the master is abating, that of the slave is rising from the dust, his condition mollifying, the way I hope preparing under the auspices of heaven, for a total emancipation, and that this is disposed, in the order of events, to be with the consent of the masters, rather than by their extirpation.”

Formed in 1785, the New York Manumission Society chose John Jay as its first president, a position he held for five years. (Alexander Hamilton, its second president, held the office one year, resigning upon his removal to Philadelphia as secretary of the United States treasury.) In 1786, John Jay, afterward chief justice of the United States, drafted and signed a petition to the legislature of New York, on the subject of slavery, beginning with these words: ” Your memorialists being deeply affected by the situation of those, who, although by the laws of Cod, are held in slavery by the laws of the state,” This memorial bore also the signatures of the celebrated Alexander Hamilton; Robert R. Livingston, afterward secretary of foreign affairs of the United States, and chancellor of the state of New York ; James Duane, mayor of the city of New York, and many others of the most eminent individuals in the state. In 1787, the Pennsylvania Abolition Society was formed. Benjamin Franklin, warm from the discussions of the convention that formed the United States constitution, was chosen president, and Benjamin Rush, secretary—both signers of the Declaration of Independence and the Manumission Society founded the New York African Free School. Members provided or raised funds for teachers’ salaries, supplies, and, eventually, for the creation of new buildings to accommodate a growing student population. In addition, members were responsible for checking in on the school periodically and reporting on the state of the school and the students. In 1789,the Maryland Abolition Society was formed. In 1790, the Connecticut Abolition Society was formed. In 1791, this society sent a memorial to congress, from which the following is an extract:” From a sober conviction of the unrighteousness of slavery, your petitioners have long beheld, with grief, our fellow-men doomed to perpetual bondage, in a country which boasts of her freedom. Your petitioners are fully of opinion, that calm reflection will at last convince the world, that the whole system of African slavery is unjust in its nature—impolitic in its principles—and, in its consequences, ruinous to the industry and enterprise of the citizens of these states. From a conviction of these truths, your petitioners were led, by motives, we conceive, of general philanthropy, to associate ourselves for the protection and assistance of this unfortunate part of our fellow-men; and, though this society has been lately established, it has now become generally extensive throughout this state, and, we fully believe, embraces on this subject, the sentiments of a large majority of its citizens.” The same year the Virginia Abolition Society was formed. This society, and the Maryland society, had auxiliaries in different parts of those states. Both societies sent up memorials to congress. The memorial of the Virginia society is headed—” The memorial of the Virginia Society, for promoting the Abolition of Slavery, &c.” The following is an extract: ” Your memorialists, fully believing that ‘ righteousness exalteth a nation,’ and that slavery is not only an odious degradation, but an outrageous violation of one of the most essential rights of human nature, and utterly repugnant to the precepts of the gospel, which breathes ‘ peace on earth, good will to men;’ lament that a practice, so inconsistent with true policy and the inalienable rights of men, should subsist in so enlightened an age, and among a people professing that all mankind are, by nature, equally entitled to freedom.” About the same time a society was formed in New Jersey. It had an acting committee of five members in each county in the state. The following is an extract from the preamble to its constitution. ” It is our boast, that we live under a government founded on principles of justice and reason, wherein life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, are recognized as the universal rights of men; and whilst we are anxious to preserve these rights to ourselves, and transmit them inviolate, to our posterity, we abhor that inconsistent, illiberal, and interested policy, which withholds those rights from an unfortunate and degraded class of our fellow-creatures.”

Later, the Manumission Society lobbied to pass the 1799 law which granted gradual manumission to New York’s slaves and provided legal assistance to both free and enslaved blacks who were being abused, but not all members were abolitionists (many were slaveholders and rejected Alexander Hamilton’s suggested resolution that anyone who wanted to be a member had to free their slaves) and often disapproved of how black New Yorkers chose to celebrate these victories, including a lavish parade to celebrate the abolition of the slave trade in 1808, causing the Manumission Society to express concern that “celebrating” Abolition was “improper” and might “cause [detrimental] reflections to be made on this Society”, demanding such parades be discontinued. Black New Yorkers replied that they would do no such thing. Even so, in line with the revolutionary beliefs of many of its founders, the New York Manumission Society the Society fought on behalf of the freedom, and eventual rights, of black New Yorkers, and felt that education was vital to creating citizens that would be capable of sustaining a democracy.

African Free School No. 2, (or, the “Mulberry Street School” as it was called by its pupils) once occupied 135-137 on a plot of land surrounded by trees. Founded by the Manumission Society on Jan. 25th, 1785, The Manumission Society was an organization of esteemed men who concerned themselves not only with the emancipation of negroes, but the with the formal education of African Americans as a means of provoking public awareness to the “growing evil” of “kidnapping colored people and selling them at the south” (In the city of Philadelphia a society had already been formed to protect blacks from similar dangers there and a deputation was sent from New York to that society for information, and to procure a copy of its constitution, which assisted much in the organization of the New York Manumission Society”) and to divert black children from “the slippery paths of vice” and as a way of teaching African American children “industry” and “sobriety”, the AFS became an act of “egalitarian faith”, reflecting the Quaker roots of many of its members. At the society’s fifth meeting in August of 1785, the society took on the charge of monitoring the moral character and work ethic of free blacks. Several months later, a school for African Americans was proposed with the reasoning that education would thwart behavior reflecting badly on African Americans and masters of slaves might be convinced to manumit their slaves if they thought they could handle their freedom responsibly. The NYMS also hoped that by exposing black children to positive white role models, their pupils could undermine white “prejudice” and Black “vice.” After establishing a committee to solicit subscriptions for the school’s benefits, the society announced its plans to the general public and drew up a plan to enroll black boys and girls between the ages of five and fourteen years of age. Approval for admission depended upon a visit to the family by the school’s governing committee with a preference given those “families which are most regular and orderly in their Deportment” and children with a “posture of quiet obedience” while “in school and in the street”. In August 1788, the NYMS reported forty enrolled children “regular in their attendance” and were happy to report that they had succeeded their expectations.

Most of the AFS board members were Revolutionary leaders who came to power in New York, propagated anti-slavery sentiments, and were members of the Manumission Society. One year after the Manumission Society founded the AFS, the slave trade in New York State was “banned outright” but with loopholes, leaving the slavery issue a matter of reality for many of its African Americans at least until 1841 when slavery became the focus of sectional rivalry and the North re-defined itself as a “free” region.) Over the years five schools popped up in various locations of Manhattan, all below 19th street.

The schools were designed to educate the newly freed African American children of New York, and specifically targeted ‘respectable’ children for education. Both boys and girls attended but studied different curricula. The schools ran from eight in the morning until five in the afternoon, with a two-hour lunch break. Students learned reading, writing, mathematics, penmanship, astronomy, geography and composition. Older students taught the younger ones in a system of peer education. Stress was put on teaching correct morals to the young ones. Unlike white charity schools, exclusively reserved for the poor, the first school for “colored children” in New York, both free and enslaved, became a focal point of aspirations for a better future for New York’s African Americans. In 1788 the first African Free School enrolled fifty-six students and by 1792 a school for girls was incorporated. It was not until 1796 that a school building was purchased explicitly for the purpose of educating New York’s African American community as part of the mission of the New York Manumission Society. The original single room schoolhouse (in what is now the Financial district) opened with about forty students, many of whom were the children of slaves, under the schoolmaster Cornelius Davis and a female teacher employed to teach female students needlework. After the schoolhouse burned down in 1814, members of the New York Manumission Society raised funds for a new building on William Street. As the city of New York expanded, its population ever increasing, the demand for more schools grew. Eventually, there would be six AFS sites throughout Manhattan: AFS No. 1 (245 Williams St. near Duane); AFS No. 2 (135-137 Mulberry St.); AFS No. 3, first opened in 1831 on Nineteenth Street near Sixth Avenue, under the direction of Benjamin F. Hughes and after objections from whites in the area, relocated to Amity Street or what is now Great Jones Place near Sixth Avenue); In 1835, the African Free School was integrated into the public school system.

AFS No. 2 was one of seven schools in New York the first school to formally educate New York’s African American children, both free and enslaved, so that they might hereafter become “useful members of the community, “.

The great and noble cause of educating African Americans was far from being a popular idea. The prejudices of a large portion of the community were against it; the means in the bands of the trustees were often very inadequate, and many seasons of discouragement wore witnessed; but they were met by men, trusting in the divine. Little was done during the Revolutionary war towards ending slavery until 1781 when the legislature voted to manumit slaves serving in the armed forces. Many slaves ran off to the British during the occupation of the state. Others achieved freedom by taking up the rebels’ offer of manumission in exchange for military service. The slave population of New York City was permanently reduced. When the British and the American Loyalists pulled out of New York at the end of the war, some 3,000 blacks left with them. In 1785, when the fighting was over, New York legislature got around to the antislavery question. Though there was a clear antislavery majority in both houses, there existed a split between moderates as to how to implement emancipation. Though anti-slavery representatives, such as the Manumissions and the Democratic-Republican Party, advocated for the immediate and unconditional abolition of slavery, by now a split had developed between moderates, who favored a gradual emancipation. Anti-slavery sentiments seemed to have predominated the Assembly, and the question of civil rights for African Americans as well as the larger issue of full citizenship, suffrage and interracial marriage—all causing considerable disagreement and public political debate. Rejecting the proposal for complete abolition a bill was offered introducing gradual emancipation of slavery, providing children born of enslaved women after 1785 “be free from birth”, along with other riders including denying African Americans the right to vote or hold public office, and barring intermarriage to white persons or giving testimony against whites in any court of the state. With this bill, the second class citizenship of African Americans in New York State was almost ensured, but the Senate’s strong stance that such restrictions were not only unsound public policy but would perpetuate distrust among the races and increase civil disorder, sent the bill back to the Assembly for reconsideration. A revised bill gave in on all counts except “negro suffrage”; thus, the bill was passed with clear notice that there would be no emancipation law that did not include voting restriction. A law was also passed that year (1785) prohibiting the importation of slaves for sale with penalty of 100 pounds for the importer and freedom for the slave (persons importing slaves for personal use were not under penalty of law, but the Act of 1785 was strengthened by the provision that the sale of any imported slave would operate his freedom).

The bill also seemed to encourage the states African Americans that anti-slavery activists, including the Manumission Society, would continue to fight for emancipation on their behalf and that the “slavery issue” would soon be resolved by law as it had been in other northern states (there were almost no advertisements for runaway slaves in New York State in 1785).

Having helped prohibition of the slave trade, individual states were free to take the initiative whenever they pleased. New Jersey and Rhode Island led the way in 1787, with Massachusetts, Connecticut and New York soon following, easing restrictions on Africans already committed to slavery; and by 1788, New York legislature passed a law prohibiting the exportation of the slave trade altogether, providing freedom for any slave exported. Still, the matter of secular education of African American children in New York state was a matter persevered for implementation by the Manumission Society, or what was known as “The New York Society for the Manumission of Slaves and the Protection of such of them as had been or wanted to be Liberated”.

In Brooklyn (in the old Town of Williamsburg) Colored School #3 continued to pursue an overall policy of segregated education, even after the State of New York passed a law ostensibly desegregating the state’s schools in 1873. By 1879 the school had become overcrowded, and parents petitioned the school board for a new building. Samuel Leonard (1821-1879), who was in charge of school construction in Brooklyn from 1859 to 1879, drew up plans in the Romanesque Revival style that was popular for school buildings at that time. The building, with four classrooms for 220 students, was completed in 1881 at 270 Union Avenue, at a cost of $8,963. Soon after the school’s construction, the practice of school segregation in Brooklyn began to change.

By the 1870s, most of the black public schools had closed. By the 1880s and 1890s, African Americans, their education, and their integration into American society post-emancipation, was no longer in favor. While former Confederate States in the American South had begun to introduce Jim Crow laws, thus becoming increasingly segregated, the North had grown increasingly tired of reconciling the civil liberties of African Americans. All across America, white prejudice increased. Even among militant African Americans in the North, the need for segregated Colored Schools had become outmoded, and therefore, challenged. In fact, many Northern African American leaders, championed, the desegregation of schools by the 1880s, and aspired to abolish black public schools altogether before the close of the 19th century. 1882, Seth Low, the new mayor of Brooklyn and a reformer, appointed Phillip A. White as the first African-American member of Brooklyn’s Board of Education. White, who became the chairman of a committee in charge of the city’s colored schools, opposed forced segregation and disliked the term. 19th century civil rights activist, Timothy Thomas Fortune (an American orator, civil rights leader, journalist, writer, highly influential editor of the nation’s leading black newspaper, The New York Age) argued that the abolition of black schools in the north also threatened the jobs of black teachers. By wiping out one injustice, he argued the Board of Education was creating another injustice “as repugnant as the first.” The Brooklyn Board of Education, however, rejected Fortune’s argument, and in early 1883, directed a committee to prepare for the complete abolition of black schools without continuing to employ the twenty six remaining black teachers. In the struggle to keep black the few remaining black schools open, and their teachers employed, many black educators canvassed New York City, offering free elevated-railroad tickets to potential students, both black and white, as an inducement for them to attend their schools, most of which were a great distance from their homes. The plan was unsuccessful. Many black parents, when possible sent their children to white schools and few, if any, white parents were willing to send their children to colored schools. Black real estate broker, Simon King, sued New York City Schools in a Brooklyn court when his daughter was refused entry to any of the public schools because of her race. On an appeal in 1883, the state’s highest court decided against King. However, prominent druggist, Phillip A. White, appointed by the Mayor as a member of the Brooklyn Board of Education (Brooklyn was the only place in the state known to have blacks on its board in the 19th century) introduced a resolution directing all the city’s white public schools to except black children. By 1890, most African-American students chose to enroll in the integrated schools, and the enrollments of the colored schools had begun to decline.

White’s plan also insisted that Brooklyn schools continue to hire black teachers as well, urging more blacks to take the exams necessary to attain Brooklyn teaching certificates. As a result, the number of Black teachers increased, even during the desegregation of Brooklyn’s schools. Black teachers outside the city of Brooklyn, however, had no blacks on their school boards championing their cause, and as a result, many African American children continued to face illegal discrimination from public schools and thus went uneducated while black educators either attempted to open schools for children in their homes or were made redundant altogether ( by 1895, no Black teachers were known to have been appointed to teach in traditionally white public schools of either Brooklyn or New York City).

As Brooklyn faced one of many early waves of early gentrification, many Black neighborhoods were becoming increasingly white and parents of children insisted upon the education of their children in a new of wave of newly erected schools, as some blacks also did. However, in a joint meeting of black and white educators, it was decided that the only way to proceed with the matter of public education was to proceed with the matter of integration of public schools, students and teachers alike. African-American students were given the option to attend integrated schools, and Colored School #3 was renamed P.S. 69, making its name consistent with those of integrated schools (though white parents, for the most part, kept their children from attending the school, and as a result, it it continued to serve an exclusively African-American student body. The other two colored schools were similarly renamed.

School No 1

Scant evidence of the numerous colored schools in New York City or the ton of Brooklyn remains. However, the following might shed some light on the intellectual prowess of 19tth century students of the African Free School.

On a Thursday, Sept. 21st, 1826, Dr. Samuel L. Mitchell visited the African Free School No. 2. in Manhattan. Graduate of the University of Edinburgh Medical School, Practicing Physician, Professor of Chemistry and Natural History at Columbia College, co-founder and chief editor of the New York Medical Repository (the first scientific periodical published in the United States), founder of the foundation of New York City’s first Zoological Museum as well as one of the earliest collections in natural history at the University of New York, organizer and first president of the Lyceum of Natural History, published author, member of the New York State Legislature, Congressman and United States Senator—Dr. Mitchell interviewed one of the students, ten year old George R. Allen, and put the following questions (recorded verbatim by a third party and later published in The African Repository and Colonial Journal):

- Q. What keeps the several parts of this together?

- A. The attraction of cohesion.

- Q. What is the attraction of cohesion?

- A. It is the power, which binds the several parts of bodies together, when they are placed sufficiently near each other, or prevents them from separating, when they touch.

- Q. Has the earth any attraction?

- A. Yes sir, the attraction of gravitation.

- Q. What is the earth?

- A. It is a planet, and the third in the solar system.

- Q. What surrounds the earth?

- A. The atmosphere.

- Q. Of what does the earth consist?

- A. Of land and water.

- What shape is the earth?

- A. The earth is round.

- Q. How do you know it is round?

A.Because we can see the tops of ships mast first at sea.

A.Does the earth stand still or move?

A.It moves on its axis, and has the motion round the sun.

- Q. What takes place from these motions?

A.Its motion round the sun produces the changes of the seasons; and its motion on its axis, the succession of day and night.

- Q. If the earth turns round, why are we not turned heels up at midnight?

- A. Because the attraction of gravity draws all bodies towards the centre of the earth.

Q.Does any other planet obey the laws of gravitation?

- A. Yes sir, Mars, as well as other smaller planets called asteroids, Jupiter, etc.

- Q. Has the earth any satellite?

- A. Yes, the moon is the earth’s satellite.

Q.Has any other planet a satellite or moon?

- A. Yes, Saturn has seven and Jupiter has four, and they all gravitate towards their respective principals.

Q.Have we any antipodes?

- Yes, Sir, they are the people directly under us, they have their feet opposite to our feet.

Q.What is the nearest shape in nature to the earth?

A.An orange, because it is flattened at each end, like the poles of the world.

Q.Does not the power of gravity act upon all bodies?

- A. Yes sir.

- Q. Why then does not the earth’s attraction bring down the moon upon us?

- A. Because the greatest distance that the moon is from the earth lessens the effect of the power of gravity upon it; for, the effects of a power which proceeds from a centre, decreases as the squares of the distance from that centre increases; and as the moon is at the distance of sixty semi-diameters of the earth from the earth; the square of 60 is 36,000 and as the earth’s attraction upon the moon is 36,000 times less at the moon than at the earth’s surface, it keeps at its present distance from us.

- Q. Do you know what weight it is?

- A. Yes sir, it is the attraction of gravitation.

- Q. How much would a ball, which here weighs a pound, weigh if it were removed 4,000 miles from the earth?

- A. As it then would be double the distance from the centre of gravity, the square of 2 is 4, and according to the rule I mentioned just now, the ball would weigh but a quarter of a pound, or one fourth of what it weighs here.

At the conclusion of the interview, a document was drawn, dated “September, 1826” stating “The little black boy, G.R. Allen, is entitled to the credit of answering the preceding questions, in the manner stated, without previously knowing exactly what was to be propounded to him” , signed “Samuel L. Mitchell”.

We just c

We just c