A Home for Jazz in Fort Greene

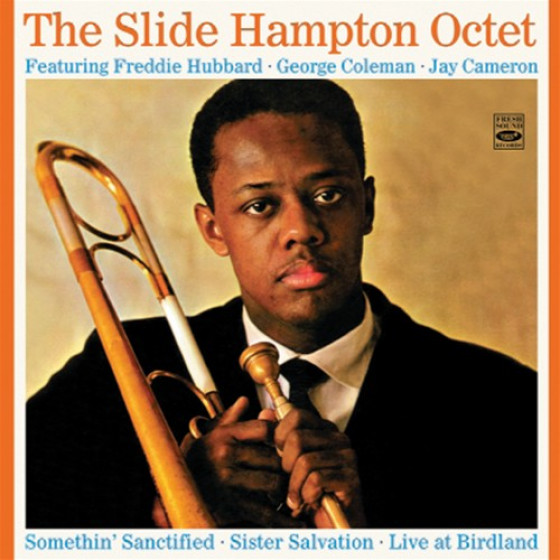

Fort Greene Jazz trombonist Slide Hampton. Image source: duna.cl

If you happen to walk anywhere within the vicinity of 245 Carlton Avenue in Fort Greene, you might hear the booming contemporary sounds of a live modern rock band, or you might hear the distant faraway complex harmonies and syncopated rhythms of a group of classic jazz musicians. The live rock music will most likely come from the teenager who lives there at present, rehearsing with his friends, to become the next great band. The jazz music, however, might actually be the result of your highly tuned auditory perception, delivering your inner ear to a musical inversion when actual jazz musicians routinely held jam sessions in that brownstone’s smoky rooms; taking the frenetic sounds of post-war be-bop and expanding them toward a modal approach reliant upon a tonal center of improvised chords. Pay close attention. You might actually be listening to Grammy Award winner Locksley Wellington Hampton (better known as “Slide Hampton”), Eric Dolphy, Freddie Hubbard, and Wes Montgomery—some of the most influential and groundbreaking jazz musicians of the 20th century who actually lived there from the late 1950s to the late 1960s.

SLIDE HAMPTON

Slide Hampton‘s distinguished career spans decades in the evolution of jazz. At the age of 12 he was already touring the Midwest with the Indianapolis-based Hampton Band, led by his father and comprising other members of his musical family. By 1952, at the age of 20, he was performing at Carnegie Hall with the Lionel Hampton Band. He then joined Maynard Ferguson’s band, playing trombone and providing exciting charts on such popular tunes as “The Fugue,” “Three Little Foxes,” and “Slide’s Derangement.” As his reputation grew, he soon began working with bands led by Art Blakey, Dizzy Gillespie, Barry Harris, Thad Jones, Mel Lewis, and Max Roach, again contributing both original compositions and arrangements. In 1959, Hampton and his wife, Althea, purchased 245 Carlton for $6,900. Less than three years after settling down there, Hampton formed the Slide Hampton Octet, which included stellar horn players Booker Little, Freddie Hubbard, and George Coleman. The band toured the U.S. and Europe and recorded on several labels.

From 1964 to 1967, he served as music director for various orchestras and artists. Then, following a 1968 tour with Woody Herman, he elected to stay in Europe, performing with other expatriates such as Benny Bailey, Kenny Clarke, Kenny Drew, Art Farmer, and Dexter Gordon. Upon returning to the U.S. in 1977, he began a series of master classes at Harvard, the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, De Paul University in Chicago, and Indiana University. During this period he formed the illustrious World of Trombones: an ensemble of nine trombones and a rhythm section. In 1998, Hampton received the Grammy Award for Best Jazz Arrangement with a Vocalist.

The 1990’s were spent doing an enormous volume of work. He continued to develop the Slide Hampton Quartet and Quintet, toured the world with the Dizzy Gillespie Alumni All-Stars, was a special advisor and arranger for the Carnegie Hall Jazz Band and arranged numerous recording projects around the world.

“(John Coltrane) used to come there all the time.” Hampton once told a reporter, “And Wayne Shorter used to live there. We had 13, 14 rooms in the house, right in Fort Greene [Brooklyn], right around the corner from Spike Lee’s father, [bassist] Bill Lee,”, continuing “a lot of musicians lived in that area. There were jam sessions and people practicing and rehearsing for years.”

Though Hampton and his wife would not sell 243 Carlton until 1985 (for $127,000) his countless collaborations over the years with the most prominent musicians of jazz afforded him a space where he could offer inexpensive rooms and impromptu rehearsal spaces for many of his jazz musician friends.

“245 Carlton Avenue–Eric Dolphy recorded a song on one of his albums called “245” , Hampton reminisced, “Robin [Eubanks, the acclaimed jazz fusion trombonist who would work with everyone from Sun Ra to Stevie Wonder to Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers] used to live there, and his brother, Kevin [jazz fusion guitarist and composer; leader of The Tonight Show band with host Jay Leno and the short lived Jay Leno show] they both lived there.”

A HOME FOR JAZZ

In the mid to late 1960’s, newspapers routinely wrote about the Fort Greene/Clinton Hill as “the slums”; the area that had long forgotten its halcyon days of the Brooklyn Dodgers, candy stores, delicatessens, dairy cafeterias and trolleys where white working class “ethnics” once occupied its spacious brownstones. Boarded up, burning down, ripped open for African Americans, Hispanics and Asians, the community slipped into dismal decay. Several hundred thousand manufacturing jobs, and even more had left the area with the closing the of the Navy Yard, and Marianne Moore, famous 20th century modernist poet who had won every prize imaginable to man, had packed up her tricorn hat and long black cape, moving out of Cumberland Avenue apartment building (where she once entertained the likes of Gertrude Stein, Alice B. Toklas, Carl Van Vechten, E.E. Cummings, Ted Hughes, Sylvia Plath, Donald Hall, and Elizabeth Bishop) and returned to Greenwich Village.

Hardly newsworthy was the fact that Brooklyn’s downtown area was also becoming a well-known neighborhood where many jazz musicians began to live, including Grammy Award winning epicenter of ever given to the dingy if not cool jazz era of Fort Greene and Clinton Hill, where Grammy award winning jazz musician, Locksley Wellington Hampton, better known as Slide Hampton, lived at 245 Carlton Avenue between DeKalb and Willoughby. Hampton’s late night jazz sessions became so famous, Eric Dolphy titled an original tune—“245”– on his 1960 album “Outward Bound”. The area was once so renown for its resident jazz artists, musician Don Cherry titled his 1960 album, “Where Is Brooklyn?”

245 Carlton Ave, as seen in 1940. Credit: NYC Archives.

According to “Brooklyn Buzz, the house Hampton owned “between the 1950s and 1970s… remained a center of jazz activity and innovation.” Three of the genre’s biggest names—Eric Dolphy, Freddie Hubbard and Wes Montgomery—even created and lived together in its communal household. Slide says he had a big room in the basement, where he hosted jazz sessions. “And everybody came to those jam sessions,” he said. ” Gerry Mulligan and Bill Lee. A lot of musicians came because they always took any opportunity they could to come to a jazz session. That was very important at the time. ”The house has witnessed a backstage thread in jazz history that few know about. Jam sessions and non-stop talks about music influenced musicians that would expand the boundaries of each of their instruments.“ Slide was always very supportive of younger players like myself and very generous with tips on how to deal with the trombone,” said Jerry Tilitz, a trombonist, composer and vocalist originally from Brooklyn but presently residing in Hamburg, Germany“ It was a house full of musical inspiration,” said Hampton. “We were all composing music in some way. There was inspiration all over the place towards music and composition. Hampton, 89, an African-American trombonist whose career spans decades in the history of jazz, and brought him worldwide recognition, represents the influence of a definitive chapter of contemporary jazz and improvised music; a chapter dominated by bebop, a form of improvisation that emerged in the late 1940s led by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie.

BUILDING A MUSIC COMMUNITY

Hampton wasn’t the only jazz musician to have once lived in the area. The late Betty Carter, a Grammy award winning Jazz singer known for her improvisational technique, scatting and other complex musical abilities, vocal talent, and imaginative interpretation of lyrics and melodies, once owned 117 Saint Felix Street, where she lived from 1972 until her death in 1998. from 1984 until his death in 2018, Cecil Taylor, American avant-garde jazz musician and pioneer of free jazz, owned the house at 135 Fort Greene Place; and Lester Bowie, jazz trumpeter, composer; member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians and co-founder of the Art Ensemble of Chicago, and inductee into the Down Beat Jazz Hall of Fame, lived at 204 Washington where he died in 1999. For decades 135 Fort Greene Place was the home of renowned avant-garde jazz pianist Cecil Taylor and lived there until his death in 2018 at the age of 89. The Fort Greene, Clinton Hill area has also, at one time or another, been home to other great jazz musicians, including Max Roach, Randy Weston, Wynton and Branford Marsalis, Gary Bartz, Bill Lee, and contemporary jazz singers such as Carla Cook.

Slide Hampton 1961 album cover. Credit: Freshsoundrecords.com

Long before winning two Grammy Awards and the prestigious National Endowment for the Arts’ Jazz Masters Award, Hampton bought 245. The house, built in 1899, served as a harbor for a select group of jazz legends that at some point inhabited or visited this classic Fort Greene brownstone, where jazz sessions were routinely held. ”Everybody came to those jam sessions,” Mr. Hampton told an interviewer, ‘Gerry Mulligan and Bill Lee. A lot of musicians came because they always took any opportunity they could to come to a jazz session. That was very important at the time.” “Slide was always very supportive of younger players like myself and very generous with tips on how to deal with the trombone,” said Jerry Tilitz, a trombonist, composer and vocalist originally from Brooklyn but presently residing in Hamburg, Germany. In fact, there was a time when the Fort Greene , Clinton Hill area not only had famous jazz musician residents, but a number of legal and illegal jazz nightclubs as well. According to photographer, Jimmy Morton Sr., these all night haunts included “Tony’s”, a once favorite hang out spot where Max Roach, Miles Davis, Gig Gryce and Charles Mingus often played together. “Although [Monk] was playing at Tony’s, [Tony’s] could not advertise [Monk].”, Morton told a large crowd at the Weeksville Heritage Center, because he “didn’t have a cabaret license.:”

THE BAND PLAYED ON

From 1940 to 1967, the New York Police Department issued regulations requiring musicians and other employees in cabarets to obtain a New York City Cabaret Card, and musicians such as Chet Baker, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, and Billie Holiday had their right to perform suspended at various nightclubs; a law that disproportionately affected the careers of many African American jazz musicians. Club owners were not allowed to advertise the appearance of artists without a license, and artists without a license were not allowed to perform in clubs where alcohol was served. Many black jazz musicians either toured Europe, or performed in underground clubs, in order to eke out a living, and survive on meager donations. Others used lofts, and other private homes in order to hold “word of mouth” parties where they could perform and earn a wage. Artists who performed at Tony’s on Grand Avenue & Dean St., included Etta Jones, Carmen McRae, and Arthur Taylor. Morton described the audience as “mostly local Brooklynites (and die-hard jazz) fans from France (as well as) American celebrities such as the famous gossip columnist, Dorthy Kilgallen.

Tony’s may have opened in the post war-period around 1952 and remained until 1955. Slide Hampton purchased his home around 1959, and moved on from the “Jazz House” at 245 Carlton Avenue in the early 1970’s. What can never be forgotten, however, is that post-WWII Fort Greene/ Clinton Hill (and its environs) is made up of more than the departure of a celebrated poet fleeing its “slum” history; it was also home to some of the greatest jazz musicians in music history. Listen closely. You might just hear them playing, “Don Cherry’s “Where’s Brooklyn?” or, Slide Hampton and his housemates, Freddie Hubbard, Eric Dolphy and Wes Montgomery joined by Jackie Byard, George Tucker, and Roy Hynes, playing Dolphy’s “245” with bursts of incendiary genius seemingly conjured out of nowhere: that music always round you, unceasing, unbeginning, ascending buoyantly through the best of times, the worse of times and times yet to come.

Read more stories about local Black history in Fort Greene, by guest contributor Carl Hancock Rux, by clicking here.