Brooklyn’s Black Broadway

Theater has been a staple of live entertainment in America at least since early days just after this country proclaimed its independence at the close of the Revolutionary war. As early as 1866, the city’s center of theatrical activity was in Manhattan’s Union Square, before it moved thirty blocks or so uptown to what we know as Broadway today. Theaters did not arrive in the Times Square area until the early 1900s, and most came and went with alarming speed. Built mostly of wood and lit primarily by flaming gaslight, the theaters of the late 1800s were infamous firetraps.

Fire in a Crowded Theater

Such was the case on the evening of December 5, 1876, when a kerosene lamp set some scenery aflame during a sold-out holiday season performance at the Brooklyn Theatre near the corner of Washington and Johnson streets (current site of the Brooklyn Post Office at Cadman Plaza, built shortly thereafter). An estimated three hundred lives were lost, making it one of the deadliest disasters in Brooklyn history and prompting new fire laws. With the literal fires of the old gaslight days quelled, few could have anticipated another kind of fire to ignite the theatrical stage, nor could they have predicted the coming Jazz age of the 1920s and 30s; Brooklyn and African American performers to be at the center of it.

Damage after the tragic fire at the Brooklyn Theater in Downtown Brooklyn in 1876.

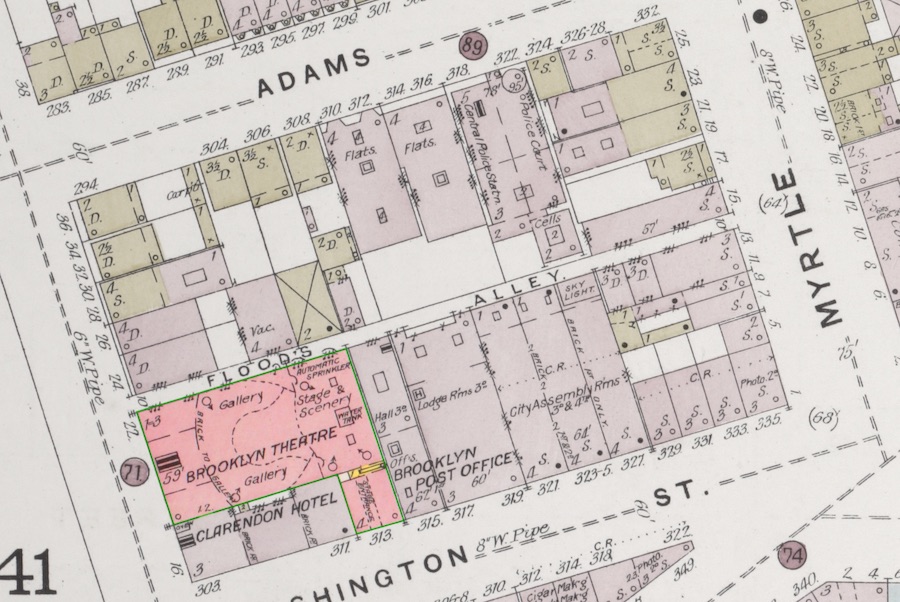

Map showing the former Brooklyn Theater off of Myrtle Avenue in Downtown Brooklyn.

A Thriving Theater District

Today the only remaining vestiges of Brooklyn’s viable theater district are the Brooklyn Academy of Music; the BAM Harvey Theater, and the former 4,000 seat Strand Theater, (repurposed and occupied by BRIC and Urban Glass).

These early century Beaux-Arts theaters and Vaudeville houses represent only a handful of handsome theaters once scattered along Fulton Street and its nearby side streets, comprising downtown Brooklyn’s Theater district.

During the Victorian era, the city of Brooklyn had become home to approximately two million residents, with at least two hundred theaters, burlesque halls, vaudeville and opera houses to accommodate them. Several first rate theaters occupied the downtown Brooklyn area—among them, the Grand Opera House; the John W. Holmes Star theater; The New Montauk Theater; and the Columbia Theater (successor to the catastrophic Brooklyn Theater). It was not until 1908, when the first subway train was opened at Borough Hall, that the decline and fall of the Brooklyn Theater set in. Many were replaced by nickelodeons and motion picture houses or torn down to make way for the expansion of the main Brooklyn Post Office and office buildings, among them, Werba’s Brooklyn Theater on the busy intersection of Flatbush and Fulton; The Brooklyn Music Hall; William Bennett’s Casino; the Gotham Theatre; and the 1,741 seat RKO Orpheum Theater (Fulton and Rockwell Place), diagonally across from the Strand and the Majestic theaters.

A Place for Brooklyn Black Actors

Hooley’s Opera House on Court and Remsen, featured “minstrel shows” (white musically adept comedians in black-face, imitating African Americans), but this brand of burnt-cork, racist entertainment was eventually replaced by actual African American musicians, composers, dancers, and singers—many of the acts having completed successful runs on Broadway or aspiring to get to Broadway. Mamie Smith, African American vaudeville singer, dancer, pianist, and actress made history in 1920 when she became the first black female recording artist (pre-dating Ma Rainy and Bessie Smith). Ms. Smith and her Jazz Hounds performed regularly at the Putnam Theater on Fulton and Grand. First opened in 1885, the Putnam first opened as the Criterion, changing its name half a dozen times before it’s balcony would suffer from a balcony fire) was renovated and reopened in 1918 as a stock burlesque house before it was demolished in 1937.

The famous African American comedy trio of WILLIAM & WALKER Co. (and Walker’s wife, Adah Overton White, a noted performer in her own right) appeared in their comedy/vaudeville musical, “Bandanna Land”, with a large a cast at the Grand Opera House in downtown Brooklyn, Brooklyn in 1908. Created by and featuring African Americans, “Bandanna Land”, was a large undertaking for Bert Williams, George Walker, and Ava Overton Walker. As a central figure on America’s vaudeville circuit, the comedy duo sang, danced and pantomimed, their act becoming a bold shift away from the traditional white black-faced entertainment that had dominated the era. The two men set up an agency, The Williams and Walker Company, to support African-American actors and other performers, create networking, and produce new works. One critic wrote for “Billboard Magazine” wrote:

“Williams and Walker have a vehicle which is making them popular… their eccentric style of character-drawing produced what is, no doubt, the highest type of negro achievement on the stage to-day. The company is made up of some clever people. In the first act there is a meeting of a corporation, which is so finished in every detail of costuming, grouping and by-play, that it is only after the fall of the curtain, that you realize how much has gone into its current presentment…If Belasco could get half the atmosphere into a production that Bandanna Land produces in such abundance, he would be rejoiced.”

Another critic in Variety magazine opined:

“‘Bandanna Land’ is a real artistic achievement, representing as it does a distinct advancement in Negro minstrelsy. Realizing, perhaps, that the white public is chronically disinclined to accept the stage negro in any but a purely comedy vein and having at the same time a natural desire to be something better than the conventional colored clown whose class mark is a razor and an ounce or two of cut glass, Williams and Walker have approached the delicate subject from a new side….’Bandanna Land’ has found substantial success at the Majestic Theatre, where it is now in its fourth week with an almost unbroken record of capacity business. No small part of the credit for this result is due to Will Marion Cook, who wrote the music, and to the splendid singing organization. The score is full of surprises, crisp little phrases that stick in the mind and are distinctly whistle-able, and several of the lyrics that go with them are excellently done.”

Actors and producers, Bert Williams & George Walker.

Moving on Up to Broadway

The New York Times proclaimed the musical comedy received a “response from the audience that was utterly deafening and had to be encored thirteen times.” Their musical moved to Broadway several months later, but sadly, it was the last show featuring the duo of Bert Williams and George Walker before Walker became ill and died in 1911, age 38. His widow, Ada Overton Walker, performing solo after the death of her husband, became known as “Queen of the Cakewalk”, and well known for her 1912 dance performance of “Salome” (in response to the Salome craze that spread through the white vaudeville circuit) on Broadway at Hammerstein’s Victoria Theater. Bert Walker continued to perform across the country including on Broadway with the Ziegfeld Follies. Walker & Williams can certainly be credited with paving the way for many African American performing artist (though all three died impoverished before the age of 50) as African American artistic expression became acceptable to white audiences.

“Shuffle Along”, which opened on Broadway in 1921, was the first major production in more than a decade to be produced, written, performed and directed entirely by African Americans, thus restoring black artistry to the mainstream of the American theater. A daring synthesis of ragtime and operetta at the onset of the Prohibition era, it “Shuffle Along” gave entertainers such as Josephine Baker, Adelaide Hall and Paul Robeson, their first big breaks at stardom; and in the many copycat black musicals to follow, gave white entrepreneurs an opportunity to use the power of their purse, and assert the evils of racism. Whites audiences flocked to see the show, as did man y African Americans (perhaps accepting a little bowing and scraping was a small price to pay for the emergence of American black artistry). Even the noted African American poet Langston Hughes called “Shuffle Along”, “a honey of a show… swift, bright, funny, rollicking, and gay, with a dozen danceable, sing-able tunes.”

Noble Sissle and chorus in Shuffle Along in 1921.

Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake’s musical took Broadway by storm in 1921 — launching the careers of Josephine Baker, Adelaide Hall and Florence Mills, among others. After a three-month run on Broadway, the show came to downtown Brooklyn’s Montauk Theater (original cast and crew in tow, including famed trumpeter, Valid Snow) and remained, in one iteration or the other, well into the 1930s (one theater critic complained it was almost “impossible to get seats”)

Sissle and Blake followed “Shuffle Along” with “Shuffle Along of 1928” along with Sissle and Blake’s new all Black revue, “The Chocolate Dandies” at Werba’s Brooklyn Theater, and in 1932, opened yet another version of the production at The Majestic Theater, starring a young Lena Horne, and all the while, maintaining a 75 member cast plus orchestra.

One of the most notable imitations to follow Sissle and Blake’s hit was “Runnin’ Wild”, book and lyrics by Flournoy E. Miller and Aubrey L. Lyles (a comedy duo who had performed in “Shuffle Along”) as well as Fats Waller, with musical accompaniment by George Gershwin, James P. Johnson. Johnson, an African American pianist and composer and pioneer of stride piano, was one of the most important pianists in the early era of recording, one of the key figures in the evolution of ragtime into what was eventually come to be known as “jazz” music. A major influence on artists such as Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Art Tatum and Fats Waller (who was also his student) the musical was noted for its syncopated upbeat ebullience.

Broadway Back to Brooklyn

After a successful 224-night run on Broadway (and a brief run in Chicago),“Runnin’ Wild” came to “Werba’s Brooklyn Theater” in 1924. Scheduled for a single night’s performance, the sold out musical ran at Werba’s on Flatbush and Fulton four weeks. One critic wrote the show was “one of the brightest and funniest Ethiopian musical shows brought to the borough!”

Werba’s Triangle Theater, seen in 1915 at the corner of Flatbush and Fulton.

One of its dance numbers in particular, roused Brooklyn audiences to their feet as they literally attempted to join in. The dance number was of course, “The Charleston.” Soon, not only Brooklyn, but the world, joined in the music and choreography of celebratory Jazz Age, with African American musicals emphasizing the era’s social, artistic, and cultural dynamism. Ironically, in Sept. of 1928, the play “Porgy” (later to be adapted into the famous Gershwin musical “Porgy and Bess”) played for a week at Werba’s. Perhaps…just perhaps, Gershwin, who had been one of the few one members of the “Runnin’ Wild” collaborative team, got the idea to set “Porgy” to music while playing with “Runnin’ Wild”: Brooklyn’s Black Broadway.

Read more stories about local Black history in Fort Greene, by guest contributor Carl Hancock Rux, by clicking here.