A Seat At the Table: Sarah Garnet

by Carl Hancock Rux

Winter’s civil twilight burnished the East River of Wallabout Bay, bringing a fresh wet cold inland off the semicircular bend of the river. January’s chill swept through the coal bunkers and the old ventilating plant, whipping around Johnson Street, from Bridge Street to Hudson avenue, climbed south uphill from Bolivar eastward through the wood-slat houses of North Portland, pressing uphill blocking the drainage systems with snow and ice, so that the entire accumulation of water, not only from the yard but from the streets above, stood in large pools of water, iced over. Sarah Garnet stood at the top of her stoop under the archway entrance of her home, supervising the shoveling of snow and ice– firmly grasping a turn-over collar at her throat, and the long winter sinner coat wrapped around a black mohair brilliantine dress he’d made herself. Shutting her doors against the frigid air, she delighted in the warmth of her house at 205 DeKalb Avenue, and the fact that she, a 71-year-old retired Black public school teacher; first African American woman public school principal; and outspoken suffragist, Mrs. Garnet, who had lived long enough to witness the emancipation of enslaved colored men and women, undoubtedly anticipated the arrival of her honored guests, and her continued participation in the discourse regarding education, economy, race, politics, and gender.

As an era of newly gained and quickly vanished civil rights for African Americans, lynching, racial violence, and slavery’s twin—sharecropping—arose as deadly quagmires on the path to full citizenship. After Reconstruction ended in 1877, the federal government virtually turned a deaf ear to the voice of the African American populace. Yet in this era Blacks were educated in unprecedented numbers: hundreds received degrees from institutions of higher learning, and a few, like W.E.B. Dubois and Carter G. Woodson, achieved doctorates. While only a small percentage of the Black populace had been literate at the close of the Civil War, by the turn of the twentieth century, the majority of all African Americans were literate, demonstrating much progress for African Americans in the last decades of the nineteenth century. Some African Americans, had chosen to leave the United States altogether. In the words of her late second husband, Henry Highland Garnet, “The nation has begun its exodus from worse than Egyptian bondage… let us not pause until we have reached the other and safe side of the stormy and crimson sea. Let freemen and patriots mete out complete and equal justice to all men, and thus prove to mankind the superiority of our Democratic, Republican government.”

A LIFE IN EDUCATION

Mrs. Garnet, however, did not seem to share her late husband’s sentiments. Her late husband had been born a slave in Maryland and, along with his family, secured his freedom in 1824, arriving in New York City in 1825, two years before the abolition of slavery in New York State. Highland Garnet entered the African Free School on Mott Street in 1826. There he met and formed lifelong friendships with James McCune Smith and Alexander Crummell, among others. In 1834, Garnet and some of his classmates formed the Garrison Literary and Benevolent Association. Perhaps drawing on his studies in navigation and seamanship at the New York African Free School, Garnet made two sea voyages to Cuba in 1828. After another sea voyage in 1829, he returned to learn that his family had separated in the hopes of escaping slave catchers. Enraged and worried, Garnet wandered up and down Broadway with a knife. Eventually friends were able to locate him and spirit him off to Long Island to hide. Garnet is perhaps most famous for his radical speech of 1843, “An Address to the Slaves of the United States of America, urging enslaved African Americans to rebel against their masters.” Frederick Douglass, who was still committed to abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison’s approach of moral suasion, spoke out against the speech, while James McCune Smith expressed admiration for it. Garnet further radicalized his position when he supported the colonization movement, which was largely unpopular among the black community. Garnet moved to England in 1850 where he continued to speak on abolitionist themes. He went to Jamaica as a missionary in 1852. In 1859 he founded the African Civilization Society and in an 1860 speech wrote of his belief that “Africa is to be redeemed by Christian civilization.” Because of Garnet’s outspoken views and national reputation, he was a prime target of a working-class mob during the July 1863 draft riots in New York City. Rioters mobbed the street where Garnet lived and called for him by name. Fortunately several white neighbors helped to conceal Garnet and his family. On February 12, 1865, Garnet became the first black person to deliver a sermon in the House of Representatives where he uttered the words quoted in the second paragraph of this article.

With his second wife, Sarah Garnet (and her accomplished younger sister) he helped found the Brooklyn based Equal Suffrage League , and served as superintendent of the Suffrage Department of the National Association of Colored Women. Appointed the U.S. Minister (ambassador) to Liberia, where he arrived on December 28, 1881, Garnet, suffered periods of physical and mental decline and expressed a great wish to die “on African soil” in Liberia, where his daughter Mary Garnet Barboza had been laid to rest years earlier. Henry Highland Garnet died February 13, 1882, of malaria, was given a state funeral by the Liberian government, and buried at Palm Grove Cemetery, in Monrovia.

FIGHTING FOR CIVIL RIGHTS

The widow Garnet, however, still had much work to accomplish for her people and her gender on American soil There were many Black men and women who, like herself, were committed to influencing an entire nation to fully realize its supposed democracy. African American women like Sarah Garnet, had long played a major role in the civil rights of African Americans. There would have to be a full commitment to the arduous work to secure civil rights and equality, no matter how many proclamations, court rulings or protests there might be.

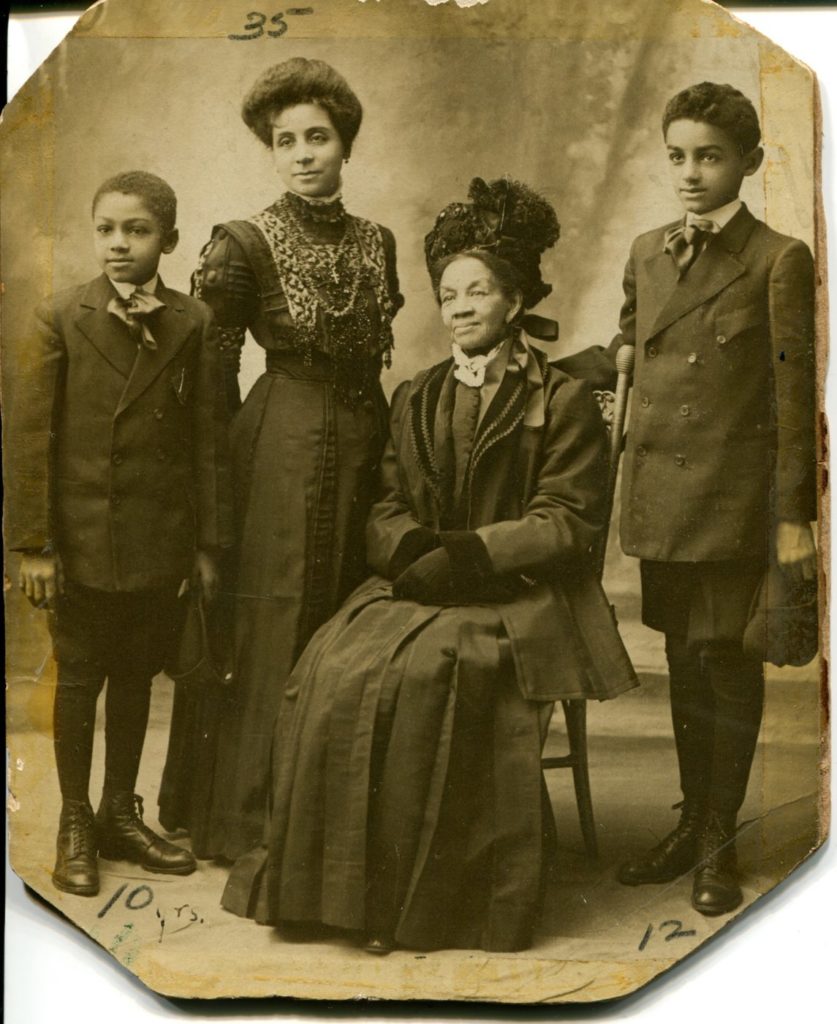

Looking at her table, stretched long across her dining room, Sarah Garnet glanced out of her parlor floor window, peering into the cold iciness of dusk, and the slow, arduous shoulders of a few of her guests braced against the wind, making their way uphill. Yes, it might be a long and difficult road to achieving full civil rights and equality for all, but it was worth the battle, if just to secure a seat at the table. Born Sarah Jane Smith in 1831, she was the eldest child of Sylvanus Smith, a wealthy Brooklyn pork merchant (described in an 1874 Brooklyn Daily Eagle article as “a colored gentleman” and “leading light in the congregation of the First Precinct” who lived at 247 Pearl Street and was reported “rich among the colored population of Navy Street and vicinity”.) and his wife, Ann Springstead Smith. Her father was one of the earliest landowners of Carrsville, (a neighboring settlement to Weeksville, Brooklyn), established a decade or so before the Civil War, comprised of successful African Americans with full voting rights who built their own churches, schools, charities and businesses (in other newspaper accounts, her father is also described as a “colored gentlemen” and “leading light in the congregation of the First Precinct”, who resides at 247 Pearl Street; is reported to be “rich among the colored population of Navy Street and vicinity”; and as early as 1842, Sylvanus Smith is also mentioned as one of ther trustees of of Colored School No. 1 on Nassau Street, near Jay Street; and the following year, as belonging to a group of trustees who petitioned the Brooklyn courts for an appropriation to purchase ground for the erection of a “Colored School”; in 1874, he is also mentioned as having been arrested for “operating an ailing horse”, and faced with imprisonment of 25 days in the Raymond Street Jail, immediately paid a ten dollar fine from his own pocket, a sizeable sum at the time).

![Where's Waldo? Williamsburg landmarks you should find [node:title] | [site:name]](https://brooklyneagle.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/colored-school-number-3.jpg)

Colored School No. 1 in Williamsburg.

THE RIGHT TO VOTE

Sarah Garnet, a committed suffragist, belonged to an unofficial sorority of African American women in the late 19th century, well into the early 20th century, who overcame the conditions of freedom, race, and gender forced upon them, not least of which was a period of exacerbated racismin the Uniuted States—with the loss of African Americans’ political rights and the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision—and reaffirmation of woman’s inferiority at the turn of the century. Most black women had to adopt ways of being women and citizens that were distinctive from their white counterparts’ and not always in keeping with Victorianism as defined in the early nineteenth century, but marked by the experience of exclusion and the challenge of meeting adversity. Also belonging to this inner circle of educated, sel-made, wealthy, African American women was Sarah Garnet’s younger siuster, Dr. Susan McKinney-Steward, the third African-American woman to earn a medical degree in the United States and the first to do so in New York State. Dr. McKinney-Steward, found her calling in medicine after her brother’s death in the Civil War and a cholera epidemic that swept through New York City in 1866 and claimed the lives of 1,137 people. Though the daughter of a wealthy pork merchant, she paid her own way through medical school by offering singing lessons and graduated valedictorian. After receiving her degree, she achieved wealth and a local reputation as a successful Brooklyn physician with an interracial clientele, specializing in pediatric care and the treatment of childhood diseases. Outside her medical practice, she agitated for social reform, advocating female suffrage and temperance. Until the early 1890s, she remained the organist for the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church where she regularly worshiped. Both of McKinney-Steward’s husbands were ministers. She was married to South Carolina minister William G. McKinney in 1871, until his death in 1894. McKinney Steward shared the home of her sister, Sarah, at 205 Dekalb Avenue, departing shortly after the death of her first husband, and her subsequent marriage in 1896 to Dr. Theophilus Steward, American author, educator, clergyman, U.S. Army chaplain, Buffalo Soldier of 25th U.S. Colored Infantry, and an ordained minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. (The Stewards would eventually settle in Ohio where both received appointments to teach at Wilberforce University, America’s first college to be owned and operated by African Americans).

The evening of Jan. 11th, 1902, Mrs. Garnet’s party party would be presided over by the toastmaster, Frederick R. Moore, editor and publisher, who worked closely with Booker T. Washington to promote the National Negro Business League; and editor and publisher of the Colored American Magazine, the most important African American newspaper in the United States. The chairman of the dinner would be prominent African American inventor, engineer, and inventor, Samuel R. Scottron, graduate of Cooper Union; community leader and outspoken advocate of trade education; advocate of racial harmony and fairness; public speaker and writer on race relations who had fought for the end of slavery of slavery in Cuba and Puerto Rico. In 1894, Sottron was appointed to the Brooklyn Board of Education and served as its only African American member for the next eight years (a staunch opponent of the segregation of the public school system, (a controversial topic in 1902 for both blacks and whites. When Sarah Garnet (nee Tompkins) began teaching in 1854, the public schools were racially segregated, including her school, the African Free School of Williamsburg; she took over leadership of Grammar School Number 4 on April 30, 1863. Now, the Sarah Smith Garnet school, P.S. 9, is located in another historic district Brooklyn’s Prospect Heights.)

The guest of honor: William F. Powell (U.S. Minister to Haiti, and Charge d’Affaires in Santo Domingo. Powell, a former Brooklynite, rose to prominence in New Jersey as a teacher and educational leader and attracted the attention of several presidents of the United States who offered him opportunities to become an American envoy. After rejecting two consular assignments, he not only served as a diplomat to Haiti but to the Dominican Republic.

Having attended public schools in Brooklyn, New York, and Jersey City, New Jersey, as well as the New York School of Pharmacy and Ashmun Institute in Pennsylvania (later known as Lincoln University) as well as the New Jersey Collegiate Institute (NJCI). In 1865, Powell graduated from NJCI and began his career as an educator when the Presbyterian Board of Missions hired him to teach at an African American school in Leesburg, Virginia. One year later, in Alexandria, Virginia, Powell founded a school for African American children and led the school for five years. Powell became principal of a Bordentown, New Jersey, school in 1875. In 1881, he interrupted his career as an educator and was employed as a bookkeeper in the Fourth Auditor’s Office of the United States Treasury. In 1881, Powell was offered a diplomatic assignment in Haiti, but he rejected it.

In 1884, Powell resumed his career as an educator when he became superintendent of schools in the fourth district of Camden, New Jersey. Under Powell’s leadership, attendance increased, manual training was included in the curriculum, and a new school for industrial education was built. In 1886, Powell relinquished his position as superintendent and taught at Camden High and Training School, a predominantly white school. This career move probably made Powell one of the first African Americans to teach in a predominantly white school in Camden as well as the rest of New Jersey. He remained at Camden High until 1894. He rejected a second diplomatic appointment in 1891 during the administration of Benjamin Harrison, the 23rd president of the United States.

In 1897, President William McKinley appointed Powell as the United States minister to Haiti, a position traditionally given to prominent black Republicans. One of Powell’s main goals in Haiti was to promote American business interests. He was very effective in his efforts to encourage U.S. business investments in the copper, railroad and timber industries. Powell also supported the educational work of Booker T. Washington by lobbying Haiti’s government to embrace the model of Tuskegee Institute for Haitian youth, and was very effective in his efforts to encourage U.S. business investments in the copper, railroad and timber industries. At the end of his tenure in Haiti, Powell had survived a planned assassination, and upon returning to America, belonged to a small but elite group of African American New Yorkers, which included Sarah Garnet and her late husband, Henry Highland Garnet, who despite their material comfort, stood at the vanguard of the fight for black civil rights.

In 1907, five years after the dinner party at Sarah Garnet’s home at 205 DeKalb Avenue, the Equal Suffrage League and the NACW (the organization Sarah J. Garnet had founded founded years earlier with her late husband and her dear sister, Dr. Susan McKinney-Steward) jointly supported a resolution supporting the principles of the Niagra Movement that advocated for equal rights for all American citizens. Four years later, Sarah Garnet traveled with her sister, Dr. Susan McKinney-Steward, to attend the inaugural Universal Races Congress of 1911, in London, England, where Dr. McKinney- Steward presented the paper “Colored American Women”. W. E. B. Du Bois also attended the conference.

Shortly after returning to New York, Sarah Garnet died on Sept. 11th, 1911, her organization for the equal rights for all Americans, dying with her. It’s mission, however, would continue for more than a century. Nine years later, after much agitation, most women received the right to vote in America. Though theoretically “equal before the law” after the nation’s emancipation proclamation of 1865, many African Americans, however, were effectively barred from voting until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965–forty-six years after Mrs. Garnet’s death. On Nov. 7th, 2020, the night United States Senator Kamala Harris was officially recognized as Vice President Elect of the United States of America, she acknowledged in her victory speech the long battle women had faced for the right to vote and to break into the highest ranks of American politics. In her acceptance speech, she acknowledged that African Americans, and especially African women, like herself, had “too often overlooked, but so often proved that they are the backbone of our democracy…” “While I may be the first woman in this office, I will not be the last,” Harris said. “Because every little girl watching tonight sees that this is a country of possibilities.”

FORT GREENE LEGACY

Perhaps that night, as the community of Fort Greene, Brooklyn, erupted in celebration, the Victorian house at 205 DeKalb Avenue (presently under renovation for its new occupants), braced itself against the autumn chill, confidant the nation was also “under renovation”, and the work of race and gender had finally reached an important inflection point in American politics: knowing the fundamental education of African American children, yet to come, had finally found its foundation. Sarah Garnet, and the many black men and women like her, had finally won a seat at the table of America.